Paper’s fast learning curve

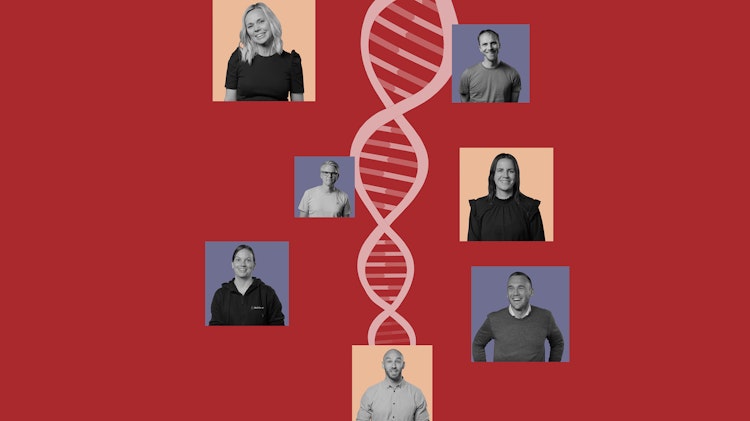

How an online tutoring startup is becoming a one-stop shop for student support

What I realized during my time in the classroom was that there was this fundamental inequity in the system.

But for Cutler and co-founder Roberto Cipriani, this was not a time for Paper to rest on its laurels. Like many high-growth startups, the company began grappling with the question of when to expand beyond tutoring and how. “We intentionally focused on broadening our offering in 2020 and began investing in other products to better support our students,” says Cipriani, who serves as CTO and COO. By the start of the 2022–23 school year, Paper was ready to debut two major new products: a streaming channel for after-school educational activities and a portal for students seeking college and career advice.“The key was finding a way of building these and rolling them out without it being too burdensome or distracting to our existing product and product teams,” Cutler says. The stakes were high both for the company and a clientele that had grown to 3 million kids in more than 500 school districts. “At 3 million students, we’re effectively the largest public educator in the U.S. given our reach,” he says.Diversifying the product portfolio is a critical moment in the life of many high-growth companies. A successful first product can put a startup on the map. But creating a defensible business and attaining status as a category-defining leader—not to mention finding ways to grow a company’s addressable market—often means expanding beyond the startup’s roots.Yet expanding beyond that core product can be treacherous. It requires investment and involves risk. It can muddy a company’s message, throw off management’s focus or siphon off engineering resources from what made the company thrive in the first place.“Moving into new products can be a giant distraction,” says Martín Varsavsky, one of Europe’s best-known serial entrepreneurs, who founded companies in fields ranging from telecom to life sciences on both sides of the Atlantic. “When these ideas come up, there always needs to be a debate. Do you implement them, kill them, or build another company.”Paper is still early in its evolution. But the story of how it has diversified its products offers an inside look at how a high-growth startup can successfully navigate the pitfalls of strategic expansion.

From educator to

entrepreneur

Cutler was a freshman at McGill University in Montreal when he created the business that would serve as a precursor to Paper. It was 2009, and Cutler sat in an auditorium with some 160 other freshmen enrolled in the university’s school of education, where students were advised to do some tutoring as a way to begin honing their teaching skills. On the spot, Cutler decided he would build a matchmaking service that paired classmates who wanted to become tutors with young students needing help.“I ran ads asking families to pay 50 bucks an hour for a private tutor, and I’d take a small cut,” Cutler says. He ran the service on an Excel spreadsheet until 2011 when a friend introduced him to Cipriani, who was working as a freelance software developer. Cipriani built back-end technologies, including payment processing and the appointment system. While in university, Cutler also founded a learning-focused summer camp that still exists today.

We recognized that we had an opportunity to invest in other offerings that would let us better support the student.

After graduating, Cutler did an eye-opening stint as a substitute teacher in the Montreal public school system. “What I realized during my time in the classroom was that there was this fundamental inequity in the system,” Cutler says. The only kids who had access to private tutors were those from families of means—and typically not those who most needed the help. Addressing that inequity became the animating idea for a new company they called GradeSlam and would change its name to Paper in 2020.“I wasn’t planning on building a big company,” Cutler says. “I was just trying to solve a problem for the students in the schools I was connected with and maybe get a full-time teaching job for myself.” Only once he and Cipriani had begun devoting themselves full-time to the cause did he realize the potential of what they had started.“It became apparent pretty quickly that the problem was way bigger than I had initially thought,” Cutler says. The unfairness he witnessed first-hand in Montreal was in evidence “at every school, everywhere. It really required a much more scalable solution.”

Students in the driver’s seat

Paper’s portfolio of products—what it decided to build and what shape each offering took—is based largely on feedback from students, teachers, and administrators. That approach to innovation in learning was embraced by Cutler and Cipriani shortly after they conceived the initial idea for the Paper online tutoring service. The founders thought sessions would take place over video chat, but student feedback caused them to pivot.“It became clear from our conversations with the students that the idea of video conferencing with some stranger was highly uncomfortable and felt very invasive,” Cutler says. Cipriani had developed some video conferencing software, but they junked it and decided on a messaging-based service. Students can upload photos and PDFs, but never do they turn on a camera. “That was very counterintuitive to me, but our engagement went up as a result,” Cutler says.

Similarly, the company’s first product expansion—which happened even before it had signed up its first paying customers—was also student-driven. Kids seeking feedback on an essay for English class would reach a live tutor and then stare at their phone while the tutor reviewed their work. “Students were asking us, ‘Why can’t we just drop off the essay and get the feedback when it’s ready,’” Cipriani says. This led to Review Center, an asynchronous essay review service, which complemented Live Help, the company’s core tutoring offering. Shortly after its debut, students pushed the service beyond the English class, uploading college admissions essays and even cover letters or resumes. In response, Paper has added staff knowledgeable about college admissions and professional resume writers to meet that need.Paper wasn’t always an easy sell. The company’s service was more expensive than ed-tech solutions others were peddling. That’s in part because, to attract high-quality tutors to its platform, it decided to eschew the gig-work model and instead offered tutors full-time employment at the company. “We wanted to create an alternative career path,” Cutler says.The company secured its first two customers in 2018, both of them in Orange County, just south of Los Angeles. The first was Laguna Beach Unified, a school district based in a well-off area and known for piloting new technologies. Shortly after, Paper heard from the neighboring district of Irvine. “They wanted to know why we were working with Laguna when they were the ones with equity issues,” Cutler says. “They’re like, ‘We’ve got super-wealthy families and we’ve got very poor families all going to school together. We need a solution like this.’” That year, Cutler says, “several of us basically moved to LA to be closer to our customers.” What began as a one-month residency ended up being a permanent office.

A portfolio that grows methodically

Serious conversations about product expansion began anew in early 2020, just before the start of the pandemic. The company’s user base was growing at a fast clip, and Paper had just received a large new venture capital infusion. “We recognized that we had an opportunity to invest in other offerings that would let us better support the student,” Cipriani says.But which of an ambitious list of options would they choose? How would they even approach the process that would lead to its decision? As Cutler and Cipriani began discussing ideas, they agreed not to spread themselves too thin. “If you’re trying to do everything at once, it’s difficult,” Cutler says.

That, along with the company’s mission—equal access to educational opportunities for everyone—kept the leadership team focused. “We had a lot of pressure from random people who would say, ‘Oh, you’ve got to add this cool, flashy feature, kids will love it,’” says Alyssa Tuman, Paper’s vice president of customer experience. “But we stayed problem focused rather than feature focused.” One advantage the company had was its close relationship with any district choosing to buy its services. “We know our customers really well, which means we know their problems really well,” Tuman says.After considering more than a dozen ideas, the team settled on what they called Camp Paper—a summer program that would serve as an online version of the camp Cutler had founded while still in university. It was different from the core services, but wouldn’t require a massive product development effort. “It wasn’t too out there,” says Cipriani, “but it wasn’t just a small iteration on what we were already doing.” And while families of means had access to a variety of summer programs, Culter says, “there was really no option available to families that couldn’t afford them.”

To ensure the rest of the company wasn’t distracted by the effort, Paper created a small, dedicated team to work on the new idea. Camp Paper launched as a summer pilot. After discussions with school administrators, it morphed into an after-school program renamed PaperLive, whose content was developed with input from districts. In September 2022, it made the service available to any of the 3 million students signed up for Paper. There’s live, weekly programming around a variety of topics, from astronomy to history to Spanish, gamified to hold the attention of those growing up watching YouTube and TikTok. “The academic piece is still critical, but it showed us that we need to make sure kids love learning,” Cutler says.Building on the success of its college essay review service, Paper also set to work on a college counseling service that would supplement the support students already received from high school guidance counselors. The marketplace soon told the company it was thinking too narrowly. “In some of our communities,” Cutler says, “70 to 80 percent of kids don’t go to four-year colleges.” They decided to expand their offering and this fall debuted Paper Accepted and Paper Hired, a college and a career prep service, respectively. Paper Math, the result of a small, strategic acquisition, launched around the same time, offering daily math challenges tailored to students’ needs.“This is a team that has been methodical in its approach and stayed true to the vision of the founders in terms of bringing education in a scalable way to the people that need help and can’t afford it,” says Ram Trichur, the Vision Fund partner who led the firm’s investment in Paper in 2022.

Lessons on expanding a product portfolio from Paper

- 1

Users know best. Everything at Paper, from its initial tutoring service to a growing portfolio of new products, was developed with input from students.

- 2

Dedicated teams. To avoid distracting other groups, Camp Paper, the company’s biggest new product initiative, was developed by a small, dedicated team—a startup within the startup.

- 3

The mission is your guide. The goal to close the inequity gap in education acted as a North Star for all of Paper’s new product ideas.

- 4

Don’t buck trends; ride them. Young people were most comfortable communicating through text; trying to force video chat on them proved a distraction.

- 5

Be patient, iterate and obsess over customer feedback. Paper Live went from video to text; Camp Paper, from summer camp to after-school program, all because that’s what customers wanted.

Building for the long term

Paper’s product portfolio and customer base have grown hand in hand. After the pandemic drove large urban districts in Boston, Atlanta, Columbus, and elsewhere to sign up with Paper in 2021, the entire states of Mississippi and Tennessee, as well as Los Angeles Unified School District, the nation’s second largest, followed suit in 2022. Paper now employs more than 2,000 tutors and is adding roughly 50,000 students every week. A financing round in February 2022 valued the company at $1.5 billion, a figure that places Paper among the top three players in the ed-tech tutoring subsector, according to Barclays.Looking back, Cutler and others say the company has managed to create a virtuous cycle: its core service has led to high student engagement, which in turn, has led to growing trust on the part of the districts, which in turn, gives Paper the permission to layer on new products. “Once we were able to overcome that barrier of getting into public education and becoming true partners with them, then it becomes, ‘Okay, how can we continue to support you in any way we can?’” Tuman says.

Reports from the field seem to bear that out. “Teachers have been pleasantly surprised by how much the students have embraced it and asked for a tutor and support in the evenings,” says Kyra Schloenbach, the chief academic officer at the Columbus (Ohio) City School District. At Val Verde Unified, north of Los Angeles, month-to-month usage of Paper is growing by 150 percent, and economically disadvantaged students account for more than three-quarters of all users. At other districts, Paper is being used to close critical learning gaps that were exacerbated by the pandemic.As the company eyes further product expansion into early childhood literacy and other areas, it’s doing so with patience. “That can be difficult to do, especially when you’re trying to grow quickly and have a lot of upsells and make more money,” says Tuman. “But we say, ‘Okay, we have to pause or else we’re going to risk burning that bridge”—a relationship with a prospective school district—“before we even have the opportunity to have a real conversation with them.’” That’s a hallmark of a company that is growing for the long-term, not for its next quarter.